Thanks to Carol Kocivar and Ed100.org for co-authoring this insightful blog.

California’s literacy crisis

By almost any standard, California is failing to meet its most basic education goal: literacy. Millions of students struggle to read.

This conclusion isn’t based on just one test. Numerous indicators document this failure. Happily, we know what to do about it. Change will require action in every school.

Start with the data

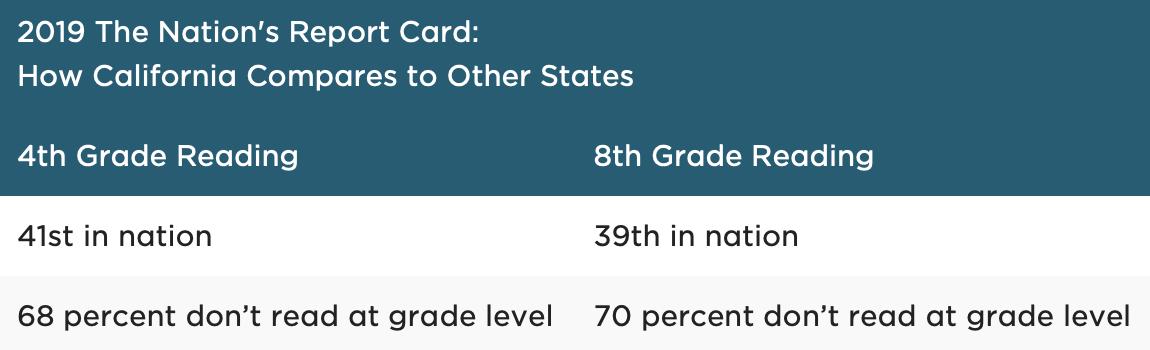

Year after year, the Nation’s Report Card (NAEP) has shown that most California students are not proficient in reading. This is the only assessment that measures what U.S. students know and can do in various subjects across the nation, states, and in some urban districts.

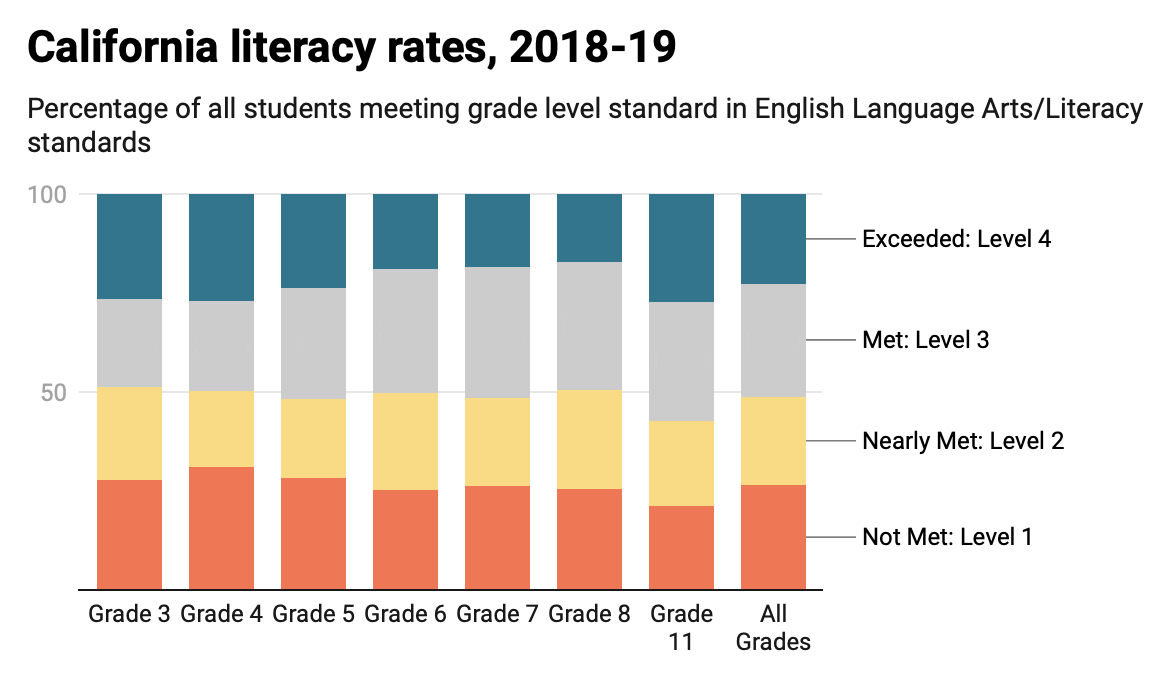

This failure isn’t just a figment of how the national test is designed. California’s Smarter Balanced Summative Assessments show similar disturbing results. At every grade level, about half of students do not meet English Language Arts Literacy Standards.

The California Reading Report Card draws similar conclusions from the CAASPP data. “… today, half of California’s students do not read at grade level. What’s worse, among low-income students of color, over 65% read below grade level. Few ever catch up.”

Diagnose the problem

The problem is not your usual suspects — poverty, lack of resources or non-English home language. The problem is how schools teach reading.

According to the California Reading Report Card:

“ …it is not the students themselves, or the level of resources, that drive student reading achievement — the primary drivers are district focus on reading, management practices, and curriculum and instruction choices.…

“The 30 top achieving districts come in all types: urban, rural, and suburban, across 10 different counties, with high-need students levels ranging from 39% to 96%. Any district can succeed at teaching reading.”

The report card was designed to measure how well schools teach reading, separate from the contributions of outside resources.

How is your school district doing? Find out here.

Embrace the science of reading

Learning to read doesn’t happen naturally — it has to be taught. Years of scientific research have revealed a great deal about how reading develops. This body of knowledge from the fields of neuroscience, cognitive psychology, education and others is referred to as the science of reading. See summaries here and here.

Replace approaches that don’t work

Even though so much is known about reading, there is a wide gap between the science and the teaching in the classroom. Recognizing the difference between typical practices and structured literacy, the kind of teaching based on science, is important.

It’s not just a matter of preference or the swing of a pendulum. Common teaching approaches rely on cueing, a practice we now understand impedes reading development. Cueing encourages children to guess words based on pictures and context clues. It is one among several problems embedded in typical teaching practices and curricula. The “Route to Reading Avoid a Lemon” video helps parents spot problematic instruction.

Why is it so hard for schools to get early reading right? Many teachers have not been trained in evidence-based methods, popular instructional materials don’t reflect the science, and districts across California have already sunk millions of dollars into teaching methods based on discredited theory.

Learn lessons from a dyslexia lawsuit

Policymakers need to look closely at the terms of a proposed settlement agreement in a federal class action lawsuit against Berkeley Unified. The plaintiffs argue, in part, that the district failed to appropriately identify children at risk of reading difficulty. Exhibit A of the settlement agreement contains a detailed proposal to develop a literacy improvement program. It includes research-based assessment plans as well as reading programs and recommends limited use of Fountas & Pinnell LLI and Reading Recovery in cases involving students with suspected reading disabilities.

What should California do?

California is not alone in its need for better reading policies. The Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) focused on literacy in its 2021 report A Nation of Readers.

The California statewide literacy task force to help all students reach the goal of literacy by third grade, by 2026, presents the opportunity to do better. Recommendations will be introduced in the 2022 legislative session. We hope they include the following:

Key Recommendations for Legislation |

|

|---|---|

| Universal screening | Screen all students K-2 for risk of reading difficulties. Many states already do short universal screenings appropriate for the students’ age and cultures. Learn more about California’s pending screening legislation SB 237 here. |

| Respond quickly to student needs | Provide guidance and support to schools with the implementation of evidence-based programs to give students the level of support they need when they need it, an approach called Multitiered Systems of Support (MTSS). A slightly struggling student needs less support than a child with more serious learning needs. English Learners may have different needs. |

| Replace outdated instruction | School districts should replace outdated literacy methods and adopt structured literacy for all students. Reading is not something that comes naturally. All students benefit from a curriculum that meets their needs in the areas of foundational skills and reading comprehension. See primer. |

| Invest in a better curriculum | Provide school districts with additional funding to invest in highly rated, culturally relevant curriculum with evidence of improving student achievement for students who struggle to read. EdReports is a good resource for researching curricula. |

| Teach educators how to teach reading | Provide ongoing professional development and coaching of teachers, administrators, and support staff in the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of instruction based in science. |

| Improve reading instruction at schools of education | Right now, too many teacher candidates graduate without learning how to teach the updated approach to reading. Education professors and education schools need to learn the updated science of reading including the California Dyslexia Guidelines and include it in teacher preparation coursework, as defined in the new California law SB 488. |

| Help parents help their children | Parents can benefit from training on how to support early readers at home. Tennessee’s recent Free Decodables to Use at Home to Build Strong Reading Skills initiative is a good example of how to extend learning at home. Families are provided free “sound out books” along with guidance for helping their children learn how to read. Schools can work with PTAs and other community organizations to support this effort. |

Megan Potente, M.Ed. is Co-State Director for Decoding Dyslexia CA, a grassroots movement made up of parents, educators and other professionals dedicated to raising awareness and improving access to resources for students with dyslexia in California public schools. Megan has 20 years of experience working in elementary education, including roles as a classroom teacher, special education teacher, reading specialist and literacy coach. She is the parent of a thirteen year old son with dyslexia and co-leads the San Francisco Dyslexia Parent Support Group.

Megan Potente, M.Ed. is Co-State Director for Decoding Dyslexia CA, a grassroots movement made up of parents, educators and other professionals dedicated to raising awareness and improving access to resources for students with dyslexia in California public schools. Megan has 20 years of experience working in elementary education, including roles as a classroom teacher, special education teacher, reading specialist and literacy coach. She is the parent of a thirteen year old son with dyslexia and co-leads the San Francisco Dyslexia Parent Support Group.